Sustaining Rural Japan

Very often, in the rapid urbanisation of cities, little thought is put towards the preservation of centuries-old cultural heritage, in favour for urban development and boosting the nation’s economy. Singapore, in its rapid urbanisation from the 1960s to 2000s, had razed down numerous heritage buildings. While this was perhaps necessary to house a burgeoning population, Singapore did realise that there is indeed value in keeping its heritage, and had pushed for conservation and adaptation of heritage buildings from the early 2000s. It is a valuable lesson that can be applied to the many rapidly-urbanising cities and countries in Asia – establishing equilibrium between urban development, economic gain, and preservation of our cultural heritage.

Prior to my visit to Japan as a representative from Singapore for the Japan Foundation programme for ASEAN Young Intellectuals in December 2015, my impressions of Japan (having visited the country a decade prior) were a country very much focused on sustainable urban development and preservation of cultural heritage, even in the face of rapid urbanisation. Japan, as it were, would have found the equilibrium between embracing capitalism and understanding the value of cultural heritage. I had not realised, however, that there was a real problem of “disappearing” villages, in that they were not sufficiently populated – or rather, the population was not replacing itself quickly enough – to continue to sustain.

Rural Japan – disappearing into the sunset?

As an architect and urban planner focused on sustainability, my interests were in identifying the infrastructural issues that lead to this phenomenon, and perhaps suggest possibilities as to how good planning of villages may help to arrest this situation. In working with fellow delegates from ASEAN – experts in population and Japanese culture on my trip to Japan – these strategies thus became more focused.

Observations in Japan

From December 9th to 18th, at the onset of the Japanese winter, we visited Tokyo, Noto Peninsula and Kanazawa. Tokyo, a bustling, thriving global metropolis, was clearly different from Noto, a convivial and comfortable sea-town hugging the Japan Sea. On the urban density scale, Kanazawa sat comfortably in the middle. Tokyo, in its glass-and-concrete jungle, seemed at times foreboding, with its residents constantly moving in flux. In contrast, Noto, with its crafted low-rise buildings and traditional houses, felt rather inviting. We were constantly engaged by the locals, querying our presence in tourist-barren Noto Town, and were also asked on how we would suggest improvements in the lifestyles and long-term sustainability of Noto Town. Rural Japan, with its heritage, cuisine and warm people, was rather charming.

Scenes from Noto Town

The Roots of the Issue: Rural-Urban Migration and Rural Depopulation

As in most urban environments, people living in the city are subjected to multiple modes of stress, most of which are presumably work-related. Long working hours and lack of social contact are the norm, and it is no different in the larger Japanese cities. The youth eschew marriage, in pursuit of careers, or simply deem marriage as unnecessary in the modern urban landscape. As a result, urban populations tend not to reproduce, and indeed in Japan, the population rate is well below the replacement rate.

The rural areas fare better in terms of stress levels, and rural environments are typically more conducive for family life. However, the youth tend to find the draw of urban life more alluring, in terms of lifestyle draws and career opportunities. As a result, rural-urban migration tends to happen, leading to diminishing rural populations. Elementary schools have started to shut down, traditional crafts and industries have dwindled, and local cultures thus begin to vanish.

Senmaida Rice Fields, Noto Peninsula

Senmaida Rice Fields, Noto Peninsula

Retaining the Population by Sustaining Economies

In Noto, major industries include fisheries, farming and lacquerware production. More recently, a small percentage of the younger population have returned from the city, engaging in organic farming as well as setting up wineries, a trade which was never synonymous with Japan. However, the practices for the traditional industries remain fairly traditional, with technology yet to be embraced, and production mostly limited for local consumption. Exposure to these products, thus, is usually limited to the prefectural region or at best, within Japan itself.

Organic farm in Noto Town

Organic farm in Noto Town

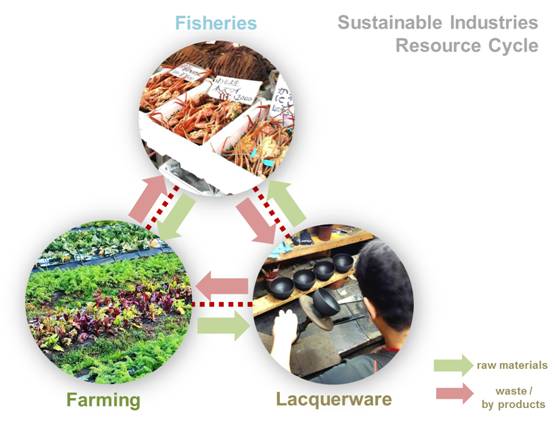

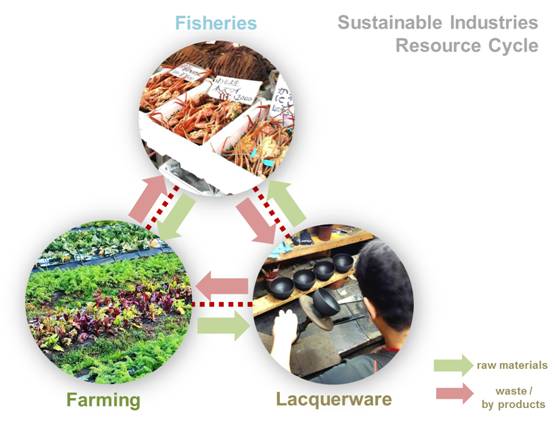

One possible aspect of retaining the rural population would be to increase the pull factors in the rural areas, possibly by making these industries more attractive. The young people, with their technological knowhow and entrepreneurial spirit, will benefit most from this scenario. Strategies could include internationalisation through export of the products, and creating niche, lifestyle-oriented industries where sustainable employment can thrive in the rural areas.Sharing of resources between industries can also be introduced. Waste materials from one industry could become the raw materials for another, and an appropriate ecosystem can be set up for this sharing to materialise. For instance, waste materials (sawdust, shredded timber chips) from the lacquerware industry may be useful for the wineries.

Unwanted or rotting wood from the fishery and winery industries can also be useful as raw material for farming, as a constituent for fertilisers. Food waste can be recycled as biofuels, such as biodiesel, useful as raw material for most industries.

In short, a sustainable material usage ecosystem can be introduced, as a small step towards a larger vision of sustained rural economies. And at a more domestic level, ‘aquaculture’, or cultivating seafood, can be encouraged at a smaller scale, where each individual household farms their own seafood for localised consumption.

A sustainable industries resource cycle: where waste materials / by-products from one industry can be shared as the raw materials for another industry

The charm of rural Japan, exemplified by Noto, remains largely hidden, as tourism is not heavily promoted. Carefully-curated tourism may be introduced to rural Japanese areas, while taking care to retain existing ecosystems and cultural values, and avoiding gentrification of these villages. Tourism as an industry could also be a sustainable economy for rural Japan, creating job opportunities and ensuring continued relevance of these areas in the regional and international eye. Tied in with the above sustainable industries, interesting tourism activities and campaigns could arise – farm stays, ecotours, fisheries expeditions, seafood preparation courses, lacquerware workshops and more!

Possible tourism mascots for Noto, as proposed by the author

Sustaining Rural Economies for a Sustained Population

The above strategies, while humble in their beginnings, may go a long way in sustaining the economies of rural Japan at large. In so doing, the young may be further motivated to remain in the rural areas which are primed for continued sustenance and careful development, while retaining their cultural currency and intrinsic charm. Conversely, young people in the urban populace may become attracted to an alternative, thriving lifestyle in the rural areas, while bringing them back to their Japanese roots.

And as Singapore and Japan begin to celebrate SJ50 – our Golden Jubilee in 50 years of cross-cultural ties – let us continue to share our thoughts and strategies in identifying problems and crafting solutions for continued sustainable environments, and the continued perpetuation of our respective populaces.

Mr Tan Szue Hann

Mr Tan Szue Hann is a registered Architect in Singapore, and currently heads the Sustainable Urban Solutions department in Surbana Jurong, Singapore. He is also the Chairman of the Institution Thrust in the Council of the Singapore Institute of Architects. His work centres on designing sustainable urban environments in Singapore and beyond, integrating architecture, engineering and urban design, while preserving cultural and economic sustainability. In September 2015, Szue Hann was awarded the BCA-SGBC Young Green Architect of the Year award.

In December 2015, he was selected as one of two Singapore representatives for the Japan Foundation Invitation Programme for Young Intellectuals in Southeast Asia, on a 10-day study trip to Tokyo, Noto and Kanazawa.